Like many readers, I am of a certain “vintage” (sounds a hell of a lot better than “age”) that clearly recalls the war in Vietnam. The Ken Burns series on Vietnam has resurrected many of these memories and feelings of a war that was _____________________ (readers are invited to add their own phrase).

As a young 2LT in the Pentagon – about as rare as a tick on a spaceship – I “experienced” Vietnam from a privileged penthouse many miles from a bloody battlefield in southeast Asia that cost the lives of many brave warriors.

I struggled then, and I struggle now, with trying to understand the “why” and the “why nots” of a war that took place some 50 years ago.

Like others who were in their early twenties in 1968, I didn’t have much of a choice in choosing to be on the “right side of history.” In fact, I would argue that most youngsters today would have a difficult time deciding “right” or “wrong” life choices based on such a pretentious and silly litmus test: i.e. the proper side of history.

There are many strong and well-founded opinions of the Vietnam war. I have no wish to discredit anyone’s views of this cataclysmic event on the American psyche, but merely to share some of my experiences while serving at the Pentagon from February, 1969 to February, 1971.

I worked in a relatively small group of “analysts” that provided daily intelligence briefs to the Army General Staff. While my specialty was Latin America, 7 or 8 officers in our 28 person office were focused on Vietnam. At the time of my arrival, General Harold Johnson was the U.S. Army Chief of Staff.

General Johnson took intelligence briefings very seriously and would often spend an hour or so reading the “Black Book,” which contained summaries of key intelligence analysis from “hot spots” from around the world. The “Black Book” would often run to 55 pages and featured important intelligence on the Soviet Union, China and the Middle East as well as Vietnam.

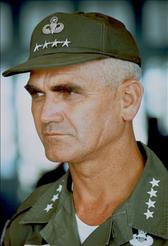

In March, 1968, President Johnson appointed General William Westmoreland as U.S. Army Chief of Staff. Instead of the extensive intelligence briefings requested by General Johnson, the Black Book was reduced to 10 or so pages with a heavy emphasis on Vietnam.

In March, 1968, President Johnson appointed General William Westmoreland as U.S. Army Chief of Staff. Instead of the extensive intelligence briefings requested by General Johnson, the Black Book was reduced to 10 or so pages with a heavy emphasis on Vietnam.

As General Joseph McChristian (Westmoreland’s G-2) required, the “Black Book” briefings were to be more like Kiplinger summaries than serious “intelligence analysis.” For those unfamiliar with Kiplinger: read “sound bites” rather than “analysis.”

From my perspective, inconsequential minutiae was far more important than the big picture. For instance, I recall a rather heated debate over the terminology of: “a drum of kerosene”; or a “kerosene drum” that was dropped from an airplane over the palace in Port au Prince, Haiti.

The fact that the “drum of kerosene” or kerosene drum” exploded seems to have been far more important that the event itself: An isolated attempt at resurrection against Francois Duvalier or Papa Doc.

While it is relatively easy to find fault in our military and political leadership, the arrival of General Westmoreland at the Pentagon signalled a major change in the way information was used to influence decisions.

Under Westmoreland, intelligence became little more than snippets of information of questionable value designed to help the General Staff respond to the latest media sensation.

Form was far more important than substance. I recall a LTC giving me (a lowly 2LT) instructions on how to properly staple a two page report: The staple should be at a 45º angle in the seal of the Department of the Army. Clearly, far too many staffies at the Pentagon looking for something to do.

While I found this amusing at the time, something far more sinister was happening at the Pentagon. Intelligence was being manipulated to prop up questionable policies and strategies. In fact, constructive debate within the E-Ring was supplemented by sycophant officers who simply parroted a self-serving agenda, which ultimately proved totally indefensible.

When looking at the war in Vietnam dispassionately – i.e. from the perspective of history – one can see that many mistakes in judgement occurred.

Vietnam leaves lasting scars and those that are so inclined should make up their own mind about the effects of this tragic war after viewing Ken Burns’ documentary. Personally, I find his narrative riveting and an accurate recreation of a pivotal event in American history.

Share

SEP

2017

About the Author:

Vietnam vintage US Army officer who honors the brave men and women who serve our country.